Group Works: Power Shift

Group Works: Power Shift

This entry continues a series in which I’m exploring concepts encapsulated in a set of 91 cards called Group Works, developed by Tree Bressen, Dave Pollard, and Sue Woehrlin. The deck represents “A Pattern Language for Bringing Life to Meetings and Other Gatherings.”

In each blog, I’ll examine a single card and what that elicits in me as a professional who works in the field of cooperative group dynamics. My intention in this series is to share what each pattern means to me. I am not suggesting a different ordering or different patterns—I will simply reflect on what the Group Works folks have put together.

The cards have been organized into nine groupings, and I’ll tackle them in the order presented in the manual that accompanies the deck:

1. Intention

2. Context

3. Relationship

4. Flow

5. Creativity

6. Perspective

7. Modeling

8. Inquiry & Synthesis

9. Faith

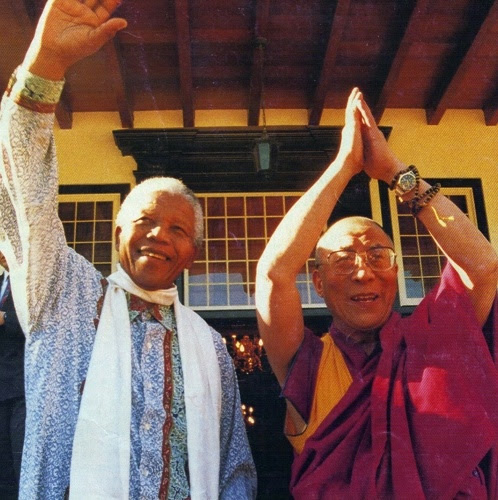

In the Relationship segment there are 10 cards. The eighth pattern in this segment is labeled Power Shift. Here is the image and thumbnail text from that card.

Critical awareness and transparency around existing power differences can, if held well, allow the group to adapt authority structures to best reflect their values or serve their aims. Sharing power isn’t always easy, but the rewards for groups who do so can be profound.

Many cooperative groups hunger for flat hierarchy and an even distribution of power. While that’s an understandable sentiment, power—the ability to get others to do something or to agree to something—is always unevenly distributed.

In my view, when it comes to power the goal of cooperative needs to be:

o Understanding how power is distributed in the group (including how that distribution shifts by topic and circumstance).

o Distinguishing between power that is used well (for the benefit of all) and power that is used poorly (for the benefit of some at the expense of others).

o Developing the capacity to examine the perception that power has been used poorly, without instigating a fire fight or inciting a witch hunt.

o Enhancing the leadership capacity of members—so that an increasing percentage of the membership has the ability to use power well.

I question whether “sharing power” is the right phrasing, because a person with power (the ability to influence others) cannot give it to others; they have to earn it. To be sure, the group can authorize someone (or a committee) to make decisions on behalf of the whole, but if that assignment is not based on trust in the person’s (or team’s) ability to do a good job, it’s a questionable prospect.

That said, the group can intentionally support members learning to exercise power well—which, if the lessons are absorbed, will result in an increasing number of suitable people among whom to distribute responsibilities.

There is a trap that some cooperative groups fall prey to in pursuit of “adapting authority structures to best reflect their values.” If the group translates that into strict rotational leadership there can be trouble. Let’s take, for example, a group that has 24 members and meets twice a month. In the interest of purposefully distributing the power of running plenaries, the group may adopt the practice of rotating facilitation such that everyone is expected to do it once annually.

On the one hand this is eminently fair and serves the goal, yet it places the plenary at risk. For one thing, not everyone is equally skilled at facilitation, nor does everyone aspire to be good at it. Thus, on those occasions when you have people uncomfortable and/or unaccomplished in the role, you’re taking a chance that the quality of the meeting can survive amateur-hour leadership. Is that smart?

For another thing, one of the hallmarks of cooperative groups is disinterested facilitation, where the facilitator is not a significant stakeholder on the topics being addressed.

If facilitation assignments are made ahead of the agenda being drafted—maybe members facilitate in alphabetical order and everyone knows their turn months ahead, which protects against someone being on vacation at the wrong time—this becomes facilitation roulette. It’s inevitable that this approach will occasionally result in a inadvertent conflict of interest, at which point bye bye neutrality. Now what?

Sure, you can scramble to produce a substitute facilitator but that undercuts the Power Shift You can see the problem.

Better, I think, is to encourage all members to develop facilitation skills, but to twist no arms (and traumatize no psyches) by making this mandatory.

Further, I think cooperative groups would be wise to invest resources in training members in facilitation, and then giving them assignments in relationship to their skill (and appropriate for their neutrality).

Think of this as a template for shifting power with discernment.

Category: Community Culture

Tags: Group Process

Views: 516